When I posted that I’d started blogging again, Andy Thornton posted a link to an article he’s written called “Into the Woods…”. It’s a really interesting piece and made me pause to reflect.

I wondered why I stopped blogging and using social media so much a few years ago. In my head there were many reasons – a different routine, different responsibilities a lack of time and so on.

But one, if i’m honest was that I was scared.

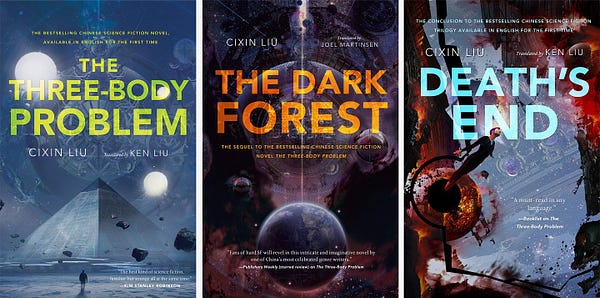

The ‘woods’ in Andy’s title refers to the Dark Forest theory which I first came across in in Liu Cixin’s books. It’s one of the most unsettling ideas you’ll find in science fiction and was created to try to answer one of the oddest questions in astrobiology. In an infinite universe which we now know has plenty of other planets, there is a very strong probability of other intelligent life, so why haven’t we made contact with any? It’s called Fermi’s Paradox.

The Dark Forest theory says the reason for this is that intelligent civilisations keep quiet. In a dark forest you don’t want the really scary beasts to know where you are, or even that you exist.

Over the last decade the open web and social media seemed to become more full of scary beasts for me. As Andy puts it:

This state of mutual suspicion and caution towards exposure is also one with echoes in our wider contemporary zeitgeist, in which rational paranoia is increasingly becoming the default mindset.

I guess I became scared of putting ideas and opinions out there. Partly in case people were rude about them, but also because I felt the chances of things being misunderstood unless you made your writing ‘perfect’ had increased.

So what’s changed? The spectre of almost everything on the web being written by ChatGPT and the like somehow fired me up. The forest is about to get much denser and darker.

It made me want to fight back and start to share things again. After all, the other way of looking after yourself in a dark forest, isn’t to hide, but to light a campfire. To do something that the scary beasts don’t understand.